East Asian History of Sci & Tech 101: The Four Great Inventions Part 2: Printing

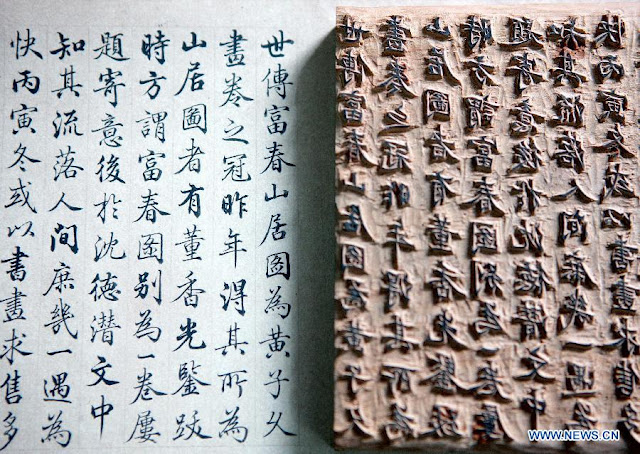

As part two of my small series on East Asian history of science and technology we are looking at one of the things that was made more viable by the first invention in this series: paper, and this is of course printing. Specifically, woodblock printing.

The first part on paper is here (I actually wrote my own article, more or less):

https://raceology.blogspot.com/2020/02/east-asian-history-of-sci-tech-101-four.html

The first part on paper is here (I actually wrote my own article, more or less):

https://raceology.blogspot.com/2020/02/east-asian-history-of-sci-tech-101-four.html

I'm a bit lazy and short on time so I will copy and paste sections from Wikipedia from this article:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_printing_in_East_Asia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_printing_in_East_Asia

The earliest surviving woodblock printed fragments are from China. They are of silk printed with flowers in three colours from the Han Dynasty (before 220 A.D.). They are the earliest example of woodblock printing on paper and appeared in the mid-seventh century in China.

By the ninth century, printing on paper had taken off, and the first extant complete printed book containing its date is the Diamond Sutra (British Library) of 868.[4] By the tenth century, 400,000 copies of some sutras and pictures were printed, and the Confucian classics were in print. A skilled printer could print up to 2,000 double-page sheets per day.[5]Printing spread early to Korea and Japan, which also used Chinese logograms, but the technique was also used in Turpan and Vietnam using a number of other scripts. This technique then spread to Persia and Russia.[6] This technique was transmitted to Europe via the Islamic world, and by around 1400 was being used on paper for old master prints and playing cards.[7] However, Arabs never used this to print the Quran because of the limits imposed by Islamic doctrine.

...

Bi Sheng (毕昇) (990–1051) developed the first known movable-type system for printing in China around 1040 AD during the Northern Song dynasty, using ceramic materials.

Clay type printing was practiced in China from the Song dynasty through the Qing dynasty.

Spread of Printing Across East Asia:

Despite the introduction of movable type from the 11th century, printing using woodblocks remained dominant in East Asia until the introduction of lithography and photolithography in the 19th century. To understand this it is necessary to consider both the nature of the language and the economics of printing.

Given that the Chinese language does not use an alphabet it was usually necessary for a set of type to contain 100,000 or more blocks, which was a substantial investment. Common characters need 20 or more copies, and rarer characters only a single copy. In the case of wood, the characters were either produced in a large block and cut up, or the blocks were cut first and the characters cut afterwards. In either case the size and height of the type had to be carefully controlled to produce pleasing results. To handle the typesetting, Wang Zhen used revolving tables about 2m in diameter in which the characters were divided according to the five tones and the rhyme sections according to the official book of rhymes. The characters were all numbered and one man holding the list called out the number to another who would fetch the type.

This system worked well when the run was large. Wang Zhen's initial project to produce 100 copies of a 60,000 character gazetteer of the local district was produced in less than a month. But for the smaller runs typical of the time it was not such an improvement. A reprint required resetting and re-proofreading, unlike the wooden block system where it was feasible to store the blocks and reuse them. Individual wooden characters didn't last as long as complete blocks. When metal type was introduced it was harder to produce aesthetically pleasing type by the direct carving method.[citation needed]

It is unknown whether metal movable types used from the late 15th century in China were cast from moulds or carved individually. Even if they were cast, there were not the economies of scale available with the small number of different characters used in an alphabetic system. The wage for engraving on bronze was many times that for carving characters on wood and a set of metal type might contain 200,000–400,000 characters. Additionally, the ink traditionally used in Chinese printing, typically composed of pine soot bound with glue, didn't work well with the tin originally used for type.

As a result of all this, movable type was initially used by government offices which needed to produce large number of copies and by itinerant printers producing family registers who would carry perhaps 20,000 pieces of wooden type with them and cut any other characters needed locally. But small local printers often found that wooden blocks suited their needs better.[48]

Despite the introduction of movable type from the 11th century, printing using woodblocks remained dominant in East Asia until the introduction of lithography and photolithography in the 19th century. To understand this it is necessary to consider both the nature of the language and the economics of printing.

Given that the Chinese language does not use an alphabet it was usually necessary for a set of type to contain 100,000 or more blocks, which was a substantial investment. Common characters need 20 or more copies, and rarer characters only a single copy. In the case of wood, the characters were either produced in a large block and cut up, or the blocks were cut first and the characters cut afterwards. In either case the size and height of the type had to be carefully controlled to produce pleasing results. To handle the typesetting, Wang Zhen used revolving tables about 2m in diameter in which the characters were divided according to the five tones and the rhyme sections according to the official book of rhymes. The characters were all numbered and one man holding the list called out the number to another who would fetch the type.

This system worked well when the run was large. Wang Zhen's initial project to produce 100 copies of a 60,000 character gazetteer of the local district was produced in less than a month. But for the smaller runs typical of the time it was not such an improvement. A reprint required resetting and re-proofreading, unlike the wooden block system where it was feasible to store the blocks and reuse them. Individual wooden characters didn't last as long as complete blocks. When metal type was introduced it was harder to produce aesthetically pleasing type by the direct carving method.[citation needed]

It is unknown whether metal movable types used from the late 15th century in China were cast from moulds or carved individually. Even if they were cast, there were not the economies of scale available with the small number of different characters used in an alphabetic system. The wage for engraving on bronze was many times that for carving characters on wood and a set of metal type might contain 200,000–400,000 characters. Additionally, the ink traditionally used in Chinese printing, typically composed of pine soot bound with glue, didn't work well with the tin originally used for type.

As a result of all this, movable type was initially used by government offices which needed to produce large number of copies and by itinerant printers producing family registers who would carry perhaps 20,000 pieces of wooden type with them and cut any other characters needed locally. But small local printers often found that wooden blocks suited their needs better.[48]

Basically printing was invented in East Asia, in China sometime in the mid-seventh century, primarily as woodblock printing. It then spread to Korea, and Japan. Soon there were hundreds of thousands of some texts or pictures that were printed. A skilled printer could print up to 2000 page double sided sheets per day. China had the largest libraries up until they were surpassed by the Europeans after Gutenberg's invention spread. Gutenberg did not invent the movable type, it was invented in China, first as ceramic, then wooden, and later metallic, although the metallic movable type also seemed to be invented in Korea. Gutenberg he may have the idea for the movable type by himself, or got the idea from missionaries who travelled to Korea. Movable type printing was not economical in East Asia due to the nature of the Chinese logographs. Thus the woodblock printing, etc., did not become obsolete until the 19th century when lithography, and photolithography technology, was invented in Europe. Also, the printing press, as a mechanized process was not invented in East Asia, but by Gutenberg. In East Asia the printing had to be done laboriously via manual means. Despite the printing press setting off a new printing revolution in Europe that later spread around the world, printing itself was invented in East Asia, where it was enjoyed for hundreds of years before being introduced anywhere else. The information it helped spread across the common people contributed to the high level of civilization enjoyed there.

Comments

Post a Comment